Table Of Contents

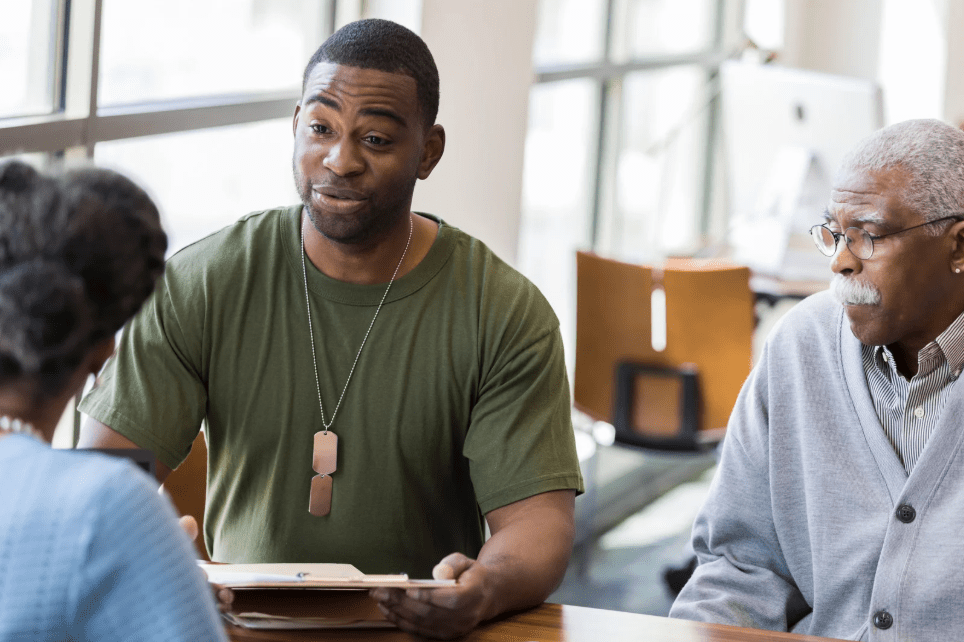

ST. PETERSBURG — St. Petersburg resident Patrick Bradley says he has a little more work to do with his therapy program before he actually “officially” retires.

That’s because the Vietnam War veteran thinks his Avian Veteran Alliance program that pairs injured birds of prey with veterans to help them deal with post-traumatic stress disorder can also be helpful to others who suffer severe stress.

And in the era of COVID-19, Bradley, who is the subject of a soon-to-be released biography, has a clear idea on how nature can help those suffering isolated-related depression from the pandemic.

The AVA program allows veterans and birds to develop a special bond.

“I am basically putting together damaged veterans with damaged birds of prey,” Bradley said. “I was putting an apex predator with an apex predator.”

“If you start to get nervous, upset, tense, in essence going into a PTSD-type fugue state if you will and then the birds react,” Bradley said. “The problem with that is you can’t pet a bird like you would a dog or a horse. So, the only way to calm the bird down is to calm yourself down. And that seems to be the biofeedback loop that we’re finding.”

Bradley says the veteran-bird pairing creates an empathetic relationship between the two as they walk together through the park that helps to focus each other.

“With PTSD, you get trapped — you keep remembering the horror that you saw,” Bradley said. “And when you pair that person with an injured animal, now you create, ‘oh, he’s with me, I’m with him. We’re together in this — it’s no longer just me.’”

The shared walk allows veteran and bird to disconnect with them being trapped, Bradley said.

Bradley, who served as Birds of Prey director at George C. McGough Nature Park in Largo, credits his work with Canadian bald eagles with saving his life, while also planting the seeds to start AVA.

After Bradley suffered a severe injury to his left wrist in 1968 during a North Vietnamese mortar attack, he was sent to Walter Reed Army Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland, where he would undergo multiple surgeries. While there, Bradley suffered the effects of PTSD, experiencing night terrors and sudden bursts of violent anger.

After healing from surgery Bradley needed to pass a psychological evaluation to be released from the hospital.

“Based on the evaluation, the psychiatrist told me that if I were to leave the hospital, I’d probably kill somebody because I was full of rage and anger,” Bradley said.

Bradley became friends with his psychiatrist — also a practicing falconer — who helped Bradley secure a grant position counting bald eagles in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan.

“It’s true — the bald eagle saved my life,” Bradley said. “This grant got me away from people and into the wilderness. I literally went in with a backpack with what I could carry — and with occasional supply drops from the Canadian government — lived there for three years and I didn’t see another human being.”

Bradley came out of the woods, he said, as someone else.

“I was a different person with a whole different mindset,” Bradley said. “Nature was it; literally surrounding yourself completely in nature is what calmed me down. The night terrors stopped and the anger wasn’t any longer apparent.”

Bradley also came out of the woods convinced he wanted to work with birds to help others who suffer PTSD.

Bradley set up his first bird therapy program at Boyd Hill Nature Preserve in St. Petersburg that paired birds of prey with veterans from Bay Pines Medical Center in St. Petersburg. Veterans came to the park twice a week to work with the birds.

Doctors at Bay Pines started to notice a difference in veterans who participated in the vet-raptor walk.

“Doctors called to ask us what we were doing, because it was making a difference,’ Bradley said. “That’s when we came up with the concept for AVA.”

In time, the program’s volunteer staff expanded from five to 70 workers.

“We had gone from an occasional school program to doing 20 programs a month,” Bradley said. “We were doing every festival that I could convince to let me in without charging me. It was a successful program and it was raising money.”

After Boyd Hill, Bradley and his son Sky — a PTSD veteran outpatient and participant in a Bay Pines Medical Center PTSD study — approached George McGough Nature Park, which had previously had a nature rehabilitation program and still had two birds of prey.

Within a short amount of time, the McGough program expanded operation to four days a week with Bay Pines Medical Center recreational therapist Elizabeth Ostrom regularly bringing wounded veteran groups to the park.

“Not only did Elizabeth keep bringing her groups out, but we started attracting other therapists to bring theirs to walk birds,” Bradley said. “We have grown the program from five to 25 birds.”

While at McGough, AVA co-founder Kaleigh Hoyt came up with the alliance name for the nonprofit to help veterans with PTSD heal.

Five years later by 2019, AVA had provided 256 outreach programs, putting an estimated 4,000 veterans through them, and raised close to $100,000 in program donations, Bradley said.

“We had done what we set out to do,” Bradley said. “AVA, for all intents and purposes, is on a slight hiatus right now.”

AVA adapting to COVID

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Bradley is working on developing a new mobile program that would bring his birds to different locations.

“We could load them up, drive to a park and meet the veterans there, put the bird on their arm and let them walk in that park,” Bradley said. “We’re fiddling with the concept to how we want to do it,” Bradley said. “I have three parks that are interested.”

Whatever AVA program is next will have to wait until COVID-19 is no longer a medical threat to those the program would treat, Bradley said.

“Right now, the Veterans’ Administration is not allowed to bring their patients,” Bradley said. “They’re not even allowed to ride on buses because of social distancing.”

Bradley is also mulling how an environmental program could be crafted to help those suffering COVID-19 induced stress produced by job loss, financial insecurity, isolation and fear.

“It’s crazy right now. People are not prepared to isolate themselves or socially distance,” Bradley said. “With this COVID-19 mess, you’ve taken away everything that people know, and they don’t handle that well. The best thing that anybody can do is go walk around the park.”

Whatever program will still use the same full-service volunteer approach used in AVA, Bradley said.

“When I volunteer for somebody, I do it seven days a week for as long as I need to; I don’t give them an hour,” he said. “For the last 11 years, I’ve been volunteering 24-7 for free.”

AVA has also generated affiliate programs around the country, receiving inquiries from other parts of Florida as well as Oregon, Washington, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, Alabama and Mississippi.

“People who have heard about us, or places that I’ve called because one of my veterans are getting out of our (AVA) program and want to know if there is some place near home that they can do it,” Bradley said.

The AVA program also received national attention in 2017 when it was included in a book titled “Vets and Pets: Wounded Warriors and the Animals That Help Them Heal.” Authors Dava Guerin and Kevin Ferris in the book tell the stories of the bonds between service members and their service animals.

After its publication, Bradley joined Hoyt and Telia Hann, one of the program’s first graduates, in visiting Kennebunkport, Maine, to discuss the book with former President George H.W. Bush and first lady Barbara Bush, who wrote the foreword for the book.

As Bradley plans his next version of AVA, his life, and the program will be featured in another new book titled “The Eagle on My Arm: How the Wilderness And Birds of Prey Saved My Life” by Dava Guerin and Terry Bivens that tells Bradley’s own story. It will be published by the University Press of Kentucky on Oct. 13.

“She (Guerin) wrote it as a biography,” Bradley said. “But to me, the most important aspect to it is the things that the AVA program has accomplished over the last 10-12 years.”

Discounts for Military Veterans 2026

Discounts for Military Veterans 2026 As a military veteran, numerous companies continue to honor...

100% VA Disability Benefits List For 2026

100% VA Disability Benefits List for 2026 When a veteran is approved for VA disability benefits,...

DIC Rates for 2026

DIC Rates for 2026 Dependency and Indemnity Compensation (DIC) can be a lifeline for surviving...